Objaśnienie:Czy macie menu po angielsku?: Różnice pomiędzy wersjami

| Linia 89: | Linia 89: | ||

}}, tłum. własne }} | }}, tłum. własne }} | ||

{{clear}} | {{clear}} | ||

| − | [[File:zupa-z-raków_3.jpg|thumb|Zupa | + | [[File:zupa-z-raków_3.jpg|thumb|Zupa <s>rakowata</s> rakowa]] |

Przedstawiciel restauracji odpowiedział na to, że będą musieli sobie porozmawiać ze swoim tłumaczem. Co pewnie należy rozumieć w ten sposób, że kierownik restauracji spróbuje w jakiś sposób nawiązać konwersację z Tłumaczem Google. | Przedstawiciel restauracji odpowiedział na to, że będą musieli sobie porozmawiać ze swoim tłumaczem. Co pewnie należy rozumieć w ten sposób, że kierownik restauracji spróbuje w jakiś sposób nawiązać konwersację z Tłumaczem Google. | ||

Wersja z 01:29, 22 mar 2022

Spis treści

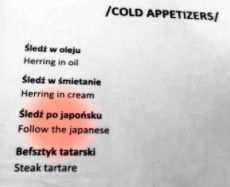

Śledź po japońsku

Śledź po japońsku to klasyczna peerelowska przystawka, która ma mniej więcej tyle wspólnego z Japonią, co pizza hawajska z Hawajami. Składa się głównie z marynowanego fileta śledziowego owiniętego wokół jajka na twardo. Być może idea zawijania surowej ryby wokół czegoś przywiodła komuś na myśl japońskie roladki maki sushi i stąd nazwa?

W każdym razie automatyczny tłumacz nie poradził sobie ze słowem „śledź”. Uznał bowiem, że to nie gatunek ryby, ale tryb rozkazujący czasownika „śledzić”. Przez to w menu, jako rzekomy angielski odpowiednik „śledzia po japońsku”, pojawiło się polecenie: „follow the Japanese”, czyli „podążaj za Japończykami”. Lepsze tłumaczenie mogłoby brzmieć: „herring in the Japanese style” czy „Japanese-style herring”, choć to też pewnie niewiele by cudzoziemcom powiedziało, ale być może wzbudziłoby bardziej ich ciekawość niż wesołość.

Śledzia po japońsku typowo układa się, w iście japońskim stylu, na pierzynce z groszku konserwowego z majonezem oraz dekoruje się plasterkami cebuli i kiszonego ogórka. Połączenie rybnych, kwaśno-słonych i tłustych aromatów czyni z tego przysmaku idealną zakąskę do wódki.

Normatyw surowcowy na 5 porcji:

Jaja ugotować na twardo, obrać. Groszek odcedzić, odsączyć. Cebulę i ogórki pokrajać w krążki. Groszek wymieszać z częścią majonezu i ułożyć z niego podstawę na półmisku lub jednoporcjowo na talerzykach. Jaja owinąć filetami śledziowymi, ustawić na postumencie z groszku. Udekorować krążkami cebuli oprószonej papryką, plastrami ogórka oraz oszprycować majonezem. Porcja potrawy powinna ważyć 100 g, w tym śledź 20 g. |

| — Krystyna Flis, Aleksandra Procner: Technologia gastronomiczna z towaroznawstwem, cz. 3, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2009, s. 88 |

Pierogi ze szpinakiem i fetą

Po zimnej przystawce pora na ciepłą; co powiecie na pierogi ze szpinakiem i fetą?

Ale moment, z jaką fetą? Chodzi pewnie o grecki ser solankowy, ale automat uznał, że do farszu dodano fetę w znaczeniu „sute przyjęcie”, bo przetłumaczył nazwę dania jako: „dumplings with spinach and celebration”. Pierogi rzeczywiście kojarzą się z uroczystym biesiadowaniem; są chociażby obowiązkowym elementem tradycyjnej wieczerzy wigilijnej (lecz może niekoniecznie ze szpinakowym nadzieniem). Zresztą samo słowo „pieróg” pochodzi od prasłowiańskiego „*pirŭ”, co znaczyło „uczta”. Pierogi są więc potrawą związaną z fetowaniem i celebracją par excellence.

Poza tym, jeśli chodzi o błędy w tłumaczeniu, to mogło być jeszcze gorzej. Tego typu wpadki zdarzają się też w drugą stronę. na przykład anglojęzycznym przedsiębiorcom sprzedającym swoje produkty Polonii amerykańskiej. Jeden z nich dostarczył do supermarketów paczki mrożonych pierogów nadzianych – jeśli wierzyć polskiemu opisowi na etykiecie – „ziemniakami ze spinaczem” („szpinak” to po angielsku „spinach”, co rzeczywiście brzmi podobnie do „spinacza”). Miejmy jednak nadzieję, że nikt nie dodaje do pierogów artykułów biurowych.

Przepis i zdjęcie pochodzą z bloga kulinarnego Posmakujto.

Składniki:

Farsz:

Jak zrobić ciasto na pierogi: Jak zrobić pierogi ze szpinakiem i fetą: |

| — Pierogi ze szpinakiem i fetą, w: Posmakujto, 20 March 2019 |

Zupa z szyjek rakowych

Po przystawkach, jak przystało na polski obiad, musi być zupa. Może zatem tradycyjny XIX-wieczny delikates, jakim jest zupa z szyjek rakowych?

Ale tu trzeba uważać. Zdarzało się bowiem, że w angielskich wersjach polskich kart dań zamiast „szyjek rakowych” pojawiał się „rak szyjki macicy” („cervical cancer”). Oto jak takie odkrycie skomentował pewien brytyjski turysta w Poznaniu:

| Nikt, kogo znam, nie miał raka szyjki, ale mogę sobie wyobrazić, że gdyby to zobaczył ktoś inny, to mogłoby mu zrobić się bardzo przykro. Jeśli chodzi o mnie, to szybko straciłem apetyt; to tłumaczenie niespecjalnie zachęca do zamówienia czegokolwiek, prawda? | ||||

— Owen Durray, cyt. w: Yusuf Bhana: Polish Restaurant Offers Cervical Cancer on Menu Due to Translation Error, w: TranslateMedia, 3 May 2013, tłum. własne

Tekst oryginalny:

|

Przedstawiciel restauracji odpowiedział na to, że będą musieli sobie porozmawiać ze swoim tłumaczem. Co pewnie należy rozumieć w ten sposób, że kierownik restauracji spróbuje w jakiś sposób nawiązać konwersację z Tłumaczem Google.

Zobaczmy, co tu się wydarzyło. To, co po polsku nazywane jest „szyjką rakową”, to po angielsku „crayfish tail”, czyli dosłownie „ogon raka”. Oczywiście zoolog powiedziałby, że to nie jest ani ogon, ani szyja, tylko odwłok. Problem w tym, że w językach słowiańskich „rakiem” przyjęło się nazywać wszystko to, co w językach zachodnioeuropejskich, w tym w angielszczyźnie, określane jest łacińskim mianem kraba, czyli „cancer” – w tym np. znak Zodiaku, a także nowotwór. Niestety, „szyjka rakowa” i „rak szyjki” może i brzmią podobnie, ale różnica w znaczeniu jest równie duża, jak między pysznym i obrzydliwym.

Jeśli ta historia Was nie odstraszyła i nadal macie ochotę na zupę rakową, to możecie wypróbować poniższy przepis. Wrzucanie żywych skorupiaków do wrzątku może wydawać się okrutne, ale zabija je to momentalnie, więc to najbardziej humanitarna metoda ich uśmiercania.

Raki szorujemy szczoteczką i bardzo dokładnie myjemy, wrzucamy je żywe do wrzątku, do którego dajemy sól i koperek. Gotujemy je pod przykryciem 6 minut. W trakcie gotowania raki zmieniają kolor na intensywnie czerwony. Po ugotowaniu i ostudzeniu wyjmujemy z nich mięso. […] Migdały sparzamy wrzątkiem i obieramy ze skórki. Ryż płuczemy, zalewamy wrzątkiem i gotujemy. Gdy jest miękki, odcedzamy go i wrzucamy do wywaru z drobiu. Dodajemy pokrojone mięso z raków, migdały, śmietanę i gotujemy, mieszamy z żółtkami, posiekanym koperkiem i doprawiamy do smaku. |

| — Maciej Kuroń: Kuchnia polska: Kuchnia rzeczypospolitej wielu narodów, Jacek Sanatorski, 2004, s. 210 |

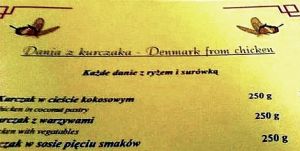

Denmark from Chicken

And now for the main course, Denmark from chicken. Is this some kind of Nordic version of chicken Kiev (or is it chicken Kyiv)? Not really. You see, "Dania" (with capital D) is the Polish name for the country of Denmark. But "dania" (with lower-case D and a marginally different pronunciation) is the Polish word for dishes or courses. So "dania z kurczaka" is not so much a single preparation as it's the title of a whole section of a menu, devoted to chicken dishes in general. And it has nothing whatsoever to do with the state of Denmark.

I suppose you still expect a recipe, though, don't you? Okay, so let's pick what is perhaps the most Polish chicken dish you can find, which is the kurczę pieczone po polsku, or liver-stuffed roasted chicken in the Polish style.

For the stuffing:

|

|

Wash the chicken, pat dry, rub with salt and set aside in a cool place for 2 hours. Prepare the stuffing: soak a stale kaiser roll in milk, squeeze the milk out and run the roll through a meat grinder together with a washed liver. […] Mix egg yolk with butter or margarine, combine with the roll-and-liver mixture, add parsley, fold in egg white beaten to a froth, season with salt and pepper. Fill the chicken with the stuffing, then truss it with pins or sew it up. Place the chicken in a roasting pan, baste with oil and bake in a preheated oven (200°C [400°F]) for 40–45 minutes. While baking, sprinkle frequently water and later with pan drippings. Carve into portions, serve along with the stuffing, potatoes and cucumber-and-cream salad. | ||||

— Zofia Surzycka-Mliczewska: Kuchnia polska, Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 2005, s. 412–413, own translation

Tekst oryginalny:

|

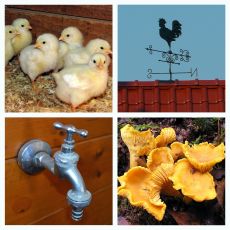

Buckwheat with Cocks Sauce

This one sounds intriguing, doesn't it? Some older folks in England might remember Cocks's Reading Sauce. And no, it wasn't used to make reading about cocks more enjoyable. It was a brand of fish sauce produced in the Berkshire town of Reading by a fishmonger whose name was James Cocks (and his heirs after him). First marketed in 1802, it was made from fermented anchovies, walnut ketchup, mushroom ketchup, soy sauce, salt, garlic and chilli peppers[1] (see my older post for more about the intertwined histories of ketchup and fish sauce). It was soon followed by and for decades competed with similar sauces, also sold in small bottles with orange labels, like the now more famous Worcestershire sauce. But eventually, the production of Reading sauce ended in 1962.[2] So it's unlikely that this is the sauce that was meant by the menu I once saw in a Polish roadside inn. Besides, while Cocks's condiment was advertised to go well with "game, wild fowl, hashes, rump steaks and cold meat",[3] it was never known to be put on heaps of boiled buckwheat.

Back to square one then. A better explanation would be that the "cocks sauce" in the menu was a result of mistranslation. The English word "cocks" has multiple meanings and so do the Polish terms "kury" and "kurki" (pronounced: Szablon:Pron, Szablon:Pron). The primary meaning of "cocks" is "male domestic fowl", also known as "cockerels" or "roosters". In modern Polish, "kury" refers to hens, but a few centuries ago it meant "roosters" instead. So was the sauce made from the meat of cockerels? Well, no.

Among the many different meanings of the English "cock", the vulgar term for the male member is particularly well known. The rooster has been a symbol of male virility in many cultures. Among Slavic languages, Bulgarian makes the same association, with "kur" referring to both the cocky bird and a man's cock ("patka" – literally, "duck" – is another vulgar Bulgarian word for the latter, which makes Bulgarians laugh every time they hear "kuropatka" – which means "partridge" in Russian and "cock-dick" in Bulgarian; gotta love these Slavic false friends). "Kur" also gave rise to the vulgar word for a prostitute (a woman whose job involves handling penes) in all Slavic languages, including Polish. But I digress; the sauce definitely wasn't made from phalli!

Besides, the Polish word was "kurki", a diminutive form of "kury". Depending on the context, it could mean freshly hatched chickens, weathercocks, stopcocks,… But none of these seem to fit in the context of sauce for buckwheat. So what does?

Chanterelles. Small, peppery, trumpet-shaped mushrooms. Their bright yellow colour might remind you of chicks, which explains why "kurki" is the common Polish name for them (see this older post for more about Polish forest mushrooms). So there you have it: buckwheat with chanterelle sauce.

Recipe and picture from the Polish cooking blog Trzeci Talerz.

Slice garlic cloves and sauté them in butter, then add chopped chanterelles. Add stock and stew the mixture on low fire for about 30 minutes. Blend in cream, which you may first mix with flour to make the sauce thicker. Add salt and pepper to taste. Cook for a few more minutes. Boil buckwheat in salted water […] Serve basted with the sauce and sprinkled with chopped parsley. | ||||

— Kasza gryczana z kurkami – kuchnia podkarpacka, w: Trzeci Talerz: Podkarpacki blog kulinarny, 2018, own translation

Tekst oryginalny:

|

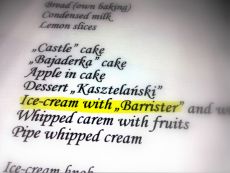

Ice Cream with Barrister

Would you like your lawyer to come along with your order of ice cream? If not, then don't worry; this is just another botched translation. The original Polish phrase is "lody z adwokatem", where "adwokat" (pronounced: Szablon:Pron) is the word that threw the machine translator off. In one sense, it does refer to a lawyer that advocates your case in a court of law, coming from the Latin word "advocatus", "the one who has been called to one's aid".

But in this case, "adwokat" is just a Polonised spelling of the Dutch "advocaat", which refers to a sweet, smooth, custardy yellow drink made from yolks, sugar and alcohol. Nobody really knows why this egg liqueur is called that. One hypothesis says it was Dutch lawyers' beverage of choice. But there's a more curious one, which claims that the name of the drink ultimately comes from a Native American word for testicles.

| When Dutch sailors found this fruit, they found out that “ahuacatl” in the Nahuatl language means “testicles” because they often grew in pairs on the trees and looked like pairs of testicles hanging off the branch. Being cheeky, they decided that they’d tell the people back home that they were called “avocaat”, which was similar to the word for lawyer. Hence we get the drink Advocaat, which was originally made with avocados by Dutch settlers in Recife. |

| — CB27: The pope's testicles…, w: Quite Interesting, 21 July 2008 |

Have you guessed what fruit they're talking about here? When the Spaniards (not Dutch) conquered Mexico and discovered the fruit, they assimilated its Nahuatl name, "āhuacatl", into their own language as "aguacate". This was later borrowed into French as "avocat" (which incidentally also means "lawyer") and into English, Dutch and many other European languages as "avocado".

But there's quite a lot to unpack here. What does the avocado have to do with an egg-based liqueur? Why did Dutch settlers in Recife, Brazil, make a drink from a fruit that is native to Mexico? What did Dutch settlers do in Brazil in the first place? And is the avocado really named after testicles?

Let's start with that last claim. Is it true? You bet it is – just as true as the fact that the Polish word "jajka" refers to both eggs and testicles, because the former look like the latter. Or that fruits with a hard shell around an edible kernel are called "nuts", because that's one of the English words for testicles, which these fruits bear an uncanny resemblance to. So yeah, it's true, but only in reverse. In fact, "avocado" is the primary meaning of "āhuacatl" in Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs), but the same word may have been used as a Nahuatl slang term for balls.[4]

As for Dutch settlers in Brazil, they actually have a pretty long history. In the first half of the 17th century, the north-east coast of Brazil was a Dutch colony known, quite unimaginatively, as New Holland. Its capital city was Mauritsstad, or Recife, now the capital of the state of Pernambuco. Even after the Portuguese recaptured Recife in 1654, Dutch migration to Brazil continued well into the 20th century.

What made Pernambuco attractive to both the Dutch and the Portuguese were its extensive sugar cane plantations (worked by African slaves). Sugar and rum – both made from sugar cane – are two of the three ingredients of advocaat. But what about the third? If what some sources, such as The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, say is true, then avocado was the original third ingredient, which lent advocaat its name. This Mexican fruit was introduced to Brazil in the early 19th century and has been grown there ever since.[5] And so, someone in Brazil combined avocado pulp, rum and sugar into a thick, sweet alcoholic drink that would find favour with the Dutch Brazilians and later, with the Dutch in the Netherlands. Attempts at recreating the drink in Europe led some Dutchperson to replace the avocado (which doesn't grow in Europe) with yolk.[6] The colour was different, but the texture may have been similar. Now, is it true? I don't know; it's not entirely implausible, but seems like a bit of stretch to me.

But hey, it's April Fool's, so yeah, 100% confirmed!

Making ice cream with advocaat may be as simple as buying a bucket of ice cream and pouring the egg liqueur on top. But if you'd like something a little more involved, then here's a recipe for home-made advocaat-flavoured ice cream.

Mix powdered milk and sugar, add 200 ml milk and bring to boil. Mix the remaining milk with cornstarch, pour into the boiling milk and make custard. Cover and let cool. Chill the cream and whip it up. While still whipping, add the custard spoon by soon, then add advocaat poured in a thin stream. Pour the mixture into a freezer-safe container and place in a freezer for at least a few hours. Mix with a fork every hour, lest ice crystals form. Serve the ice cream in bowls, doused with a little advocaat and sprinkled with almond flakes. | ||||

— Lody adwokatowe, w: Smakołyki Asi, 18 March 2022, own translation

Tekst oryginalny:

|

Apple Pie Guilty

You may have wanted to keep the barrister from the cold dessert, as apparently the hot dessert has been found guilty! Let's just hope the only thing the apple pie has been convicted of is being a guilty pleasure. The one who's really guilty here is the restaurant owner who tried to cut corners by using unverified machine translation.

The Polish adjective "winny" (pronounced: Szablon:Pron) has at least two meanings. In one sense, it comes from the noun "wina", which translates as "guilt, fault or blame". But in another sense, it derives from the completely unrelated word "wino", which means "wine". "Winey" makes much more sense in the culinary context than "guilty".

"Ciasto" ("cieście" in the locative case) is another problematic word. It may refer to a pie or cake, but also to uncooked dough or batter. As it turns out, jabłka w cieście winnym isn't a pie at all; it's apple fritters made by dunking apple slices in wine-infused batter.

And here's a recipe for the final dish of our mistranslated meal.

Peel and core apples, then cut them into round slices. Break eggs into a bowl and beat them with a mixer, gradually adding sifted flour alternating with wine. Add a pinch of salt and a tablespoon of sugar. Heat the fat on a pan, dip apples slices in the batter and brown on the pan. Arrange the fritters on a place, dust with powdered sugar. | ||||

— Renataz-Et: Jabłka w cieście z winem, w: Doradca Smaku, own translation

Tekst oryginalny:

|

Przypisy

- ↑ T.A.B. Corley: The Celebrated Reading Sauce: Charles Cocks & Co. Ltd. 1789–1962, w: Berkshire Archaeological Journal, 70, 1979–80, s. 101

- ↑ Reading Sauce, w: Glyn Hughes: Foods of England

- ↑ Sauce, w: Stuart Hylton: A–Z of Reading: Places–People–History, Amberley Publishing Limited, 2017, illustration

- ↑ Magnus Pharao Hansen: No Snopes.com, the word guacamole does not come from the Nahuatl word for "ground testicles or avocados", w: Nahuatl Studies, 10 February 2016

- ↑ Bruce A. Schaffer, B. Nigel Wolstenholme, Antony William Whiley: The Avocado: Botany, Production and Uses, CAB International, 2013, s. 18

- ↑ Darra Goldstein: The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, Oxford University Press, 2015, s. 236